This post contains affiliate links, so we may earn a small commission when you make a purchase through links on our site at no additional cost to you.

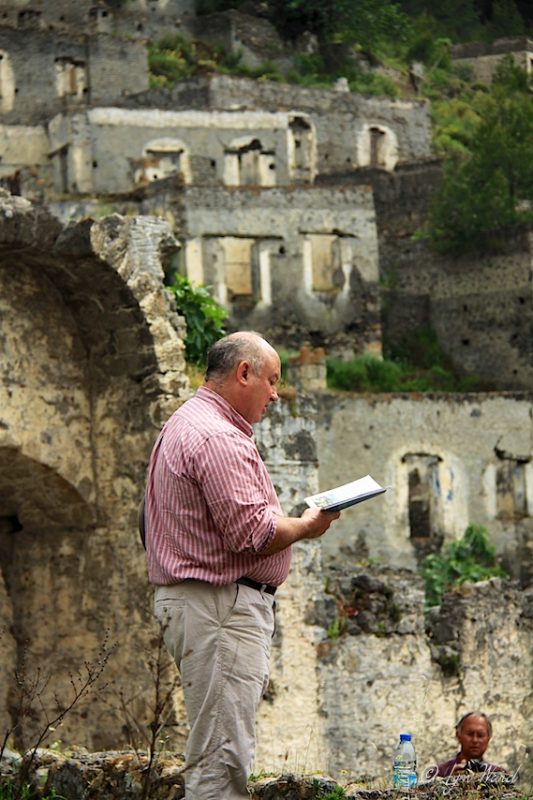

Preserved as a museum and designated by UNESCO as a “world friendship and peace village,” Kayaköy has become something of a tourist mainstay for visitors to this southwestern corner of Turkey.

However, its abandonment speaks of the bitter conflict in the wake of World War I, when Greece and Turkey fought for control of the wider region and a population exchange led to residents being unable to return to their ancestral homes.

Fethiye Time Associate Editor and previous Kayaköy resident Steve Parsley explains:

The Background

Every year, we mark the anniversary of the day the guns fell silent at the end of The Great War but, for Turkey, it was by no means peace.

By November 11, 1918, the nation had already “surrendered” – or at least decided it wanted no further part of the conflict later known as The First World War – and was negotiating the terms of its own survival with rapacious European Allies keen to carve up chunks of the former Ottoman Empire for themselves.

As Turkey as a nation was already split by internal turmoil, talks were held with two factions. The Sultan in Istanbul had always been the Turks’ figurehead in the past but firebrand and war hero Mustafa Kemal – later to take the name Atatürk – refused to be ignored, forcing the Europeans to open talks with a new, self-proclaimed republican Government in Ankara, of which he was the leading light.

However, perhaps sensing weakness in its age-old adversary, perhaps quietly encouraged by European Allies and perhaps angered by reports of ill-treatment of its subjects in Turkey during the war years, Greece seized the moment to invade. In 1919, troops landed on Turkey’s western coast and quickly pushed eastwards inland.

But they had not counted on the kind of spirit, patriotism and sheer determination to be found among soldiers fighting for their homeland and, after three years of bloodshed every bit as brutal and bitter as Flanders Fields, the Greeks were finally pushed back and the invading army crushed at a final battle on the docksides of Izmir in 1922.

The war years and the aftermath of the Greco-Turk War included the events which saw Kayaköy turn from a prosperous community to a ghost town. Within just a few years, the streets which once bustled with people from both the Muslim and Christian Orthodox faiths were silent – and have remained so until today.

The Demise of Kayaköy

Tourists visiting Kayaköy today often surmise that the community befell some sort of natural disaster. Earthquakes do occur in the region so it’s easy to assume the tumbledown buildings were ravaged by a significant seismic event long ago.

But, in truth, Kayaköy’s story is much more to do with human conflict than the power of Mother Nature.

Long before the First World War, when the Ottoman Empire stretched from the Balkans to Libya, people who lived within it and contributed to its wealth often relocated outside the boundaries of the countries we recognise today. Muslim Turks could be found in Albania, while – as skilled tradesmen and with renowned commercial acumen – Greeks could be found across Turkey, particularly in Anatolia.

At that time, communities such as Kayaköy – where Muslims mixed freely and peacefully with Greek Orthodox Christians – were by no means unusual and are perhaps depicted best in Louis De Bernière’s novel Birds Without Wings.

But that was to change during the war years between 1914 and 1918. By then, bandits had begun raiding travellers in open country or in the forests, stifling trade and making life much harder for the more far-flung communities.

The rule of law also became blurred with particular animosity towards the Greek community exacerbated by the interception of a famous letter to the British authorities in nearby Rhodes, which appeared to plead for direct international intervention in Turkey.

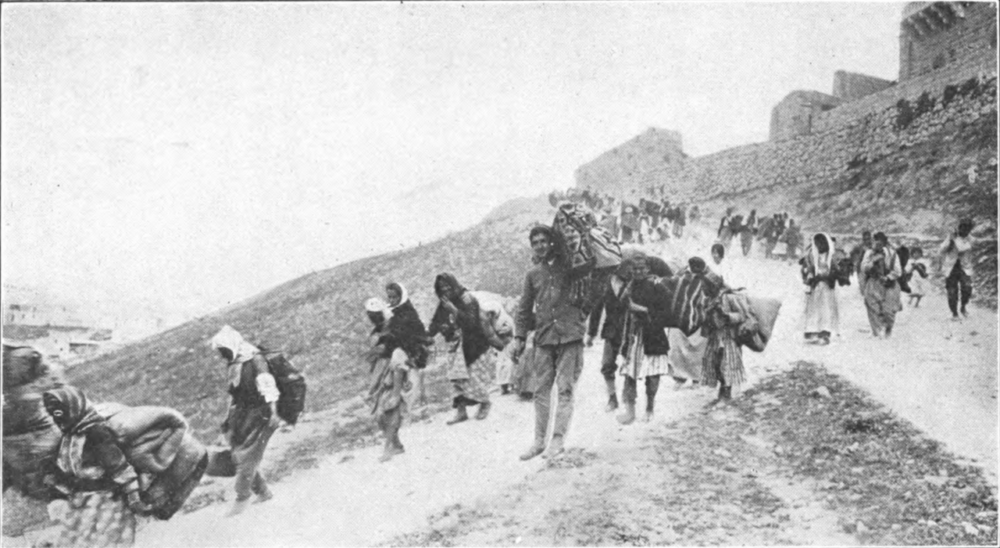

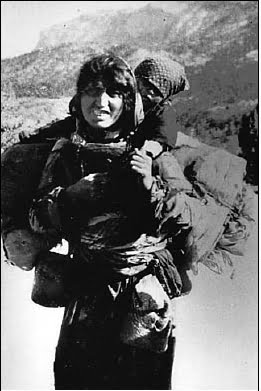

As a result, Greek families were rounded up and marched to the regional justice centre at Denizli for deportation – a gruelling trek many didn’t survive. By 1917, much of Kayaköy was already abandoned and silent, the Greeks were gone, and the houses were empty.

The Population Exchange

With so much bitterness and animosity between Greeks and Turks, particularly in the wake of the Greco-Turk war, even the leaders of the two nations realised the convenient co-existence of the Ottoman era was over.

Muslim Turks still resident in former Ottoman territories such as northern Greece were now at risk of persecution just as Orthodox Christian Greeks in Anatolia had faced growing hostility from Turks.

A relatively simple solution

With Mustafa Kemal now recognised as the leader of the new Turkey, The Treaty of Lausanne decreed that each should return to their own country with their respective Governments making up for the loss of homes and possessions.

It was a relatively simple solution in theory; Turks repatriated from Greece would simply move into homes vacated by Greeks in Turkey and vice-versa. However, in practice, the exchange was fraught with complications.

For a start, opportunistic Turks had already moved into choice homes left empty by the Orthodox Christians – including some in Kayaköy – while the criteria for repatriation was on religious lines rather than ethnicity. From 1923 onwards, this led to a sort of bloodless ethnic cleansing, which both nations were actually happy to achieve – albeit with a complete disregard for the personal circumstances of the individuals involved.

The remaining families were given hours to leave the properties they had called home for decades sometimes without explanation and without appeal. Wealthy Greek merchants who had fled Istanbul during the war years were also blocked from re-entering Turkey to take up their abandoned homes and businesses. Other races found themselves included in the exchange on religious grounds too.

After the exchange

But, even after the exchange, many of the homes in Kayaköy formerly occupied by Greek Orthodox Christians remained empty and abandoned – largely due to lifestyle differences between the former owners and those who arrived in the valley to replace them.

Many of the Turks repatriated to Kayaköy had been tobacco farmers in Albania and northern Greece and, as a result, preferred homes on the lowlands rather than perched close together on the hillside. There are reports too that they feared the homes were still occupied by the spirits of the Greeks who had left curses on the stone and timber properties.

But while the new residents showed reticence about repopulating the old village, it’s also true that it suffered from the exodus of the Greeks, who had been the backbone of the area’s skilled workforce.

Without farriers, carpenters, potters or masons, commerce simply dried up – and, with it, any semblance of the old community. Soon, all that was left were the farmsteads dotting the valley while, slowly, the old cobbled streets, churches, chapels and houses were enveloped by fig trees and mountain shrubs.

The earthquake of 1957

By the time an earthquake shook Fethiye in 1957, many of the old houses had already fallen into ruin.

Folk who had lost their homes in the earthquake were instructed to use the old houses in Kayaköy as a resource and, within a few short months, much of the timber had been stripped from them, leaving the shells still standing today.

There has been some talk of regeneration, but, as yet, little has been done. The ghost village stands silent, often shrouded in the morning mist, a poignant testament to a community where Muslim and Orthodox Christians once lived in peace – and a war that destroyed them.

Sources: Atatürk – Patrick Kinross/Hurriyet Daily News/Birds Without Wings – Louis De Bernières/Wayback Internet Archive/CNN Travel