With its nature, architecture, history and donkeys, the southeastern city of Mardin is certainly a destination that will expand your understanding of Anatolia’s cultural melting pot.

This article was written by Ernest Whitman Piper

You are bored of normal city things. I understand. You want a break from the carousel of traffic, Facebook on tiny screens and coffee shops that we call modern life. Perhaps you want to run away to the desert and never come back. I hear you. Oh man, do I ever. I have an easy fix for you: Get on a plane — it is the last modern convenience I will make you suffer through, I swear — and head to the province of Mardin in southeast Turkey.

Mardin

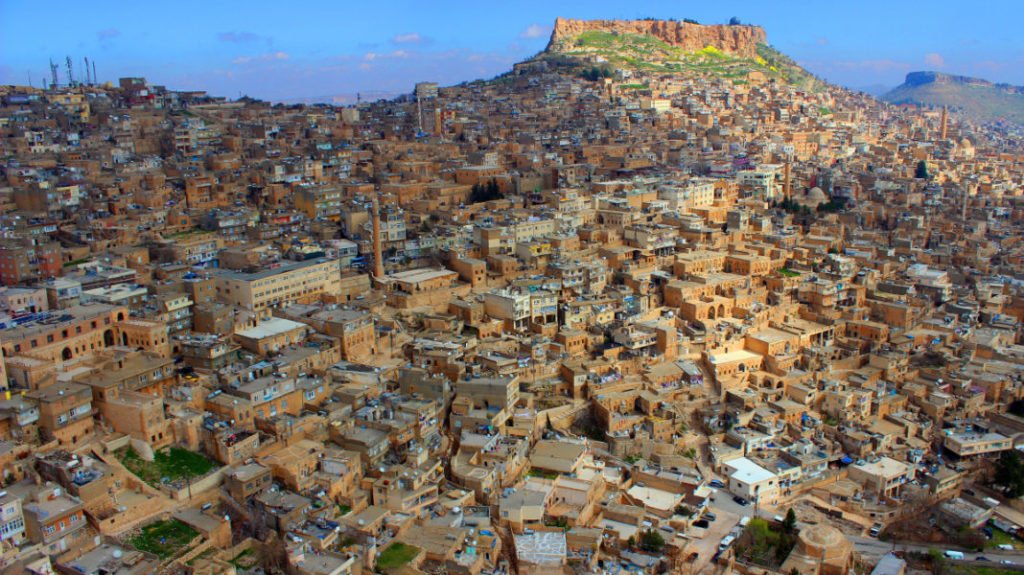

Mardin has everything you are looking for: A heady mix of cultures, spellbinding alleys of stone and an old-world approach to daily life. The city of Mardin is a swept Babylon resting on a spiral mesa, full of stone houses, ridged domes and unruly minarets seemingly designed by toymakers, all overlooking the clay-brown valleys of upper Mesopotamia. Yes, I am talking about the Fertile Crescent welcome-to-the-cradle-of-Western-civilization Mesopotamia.

The first thing we saw when we got off the bus from the Mardin airport was a donkey. The donkey was tied up near a rotary near the “new town” of Mardin, made up of the same rebar high-rises for families you see everywhere in Turkey. The donkey was next to a tan stone wall wearing a colourful saddle draped with red and white tassels. The roads were made of the same tan-coloured stone. Everything was made of that same tan-coloured stone. I liked it.

The next thing we noticed about old Mardin was that it sits on a hillside, so no matter where you stand in the city, you can always look to the south and see miles of uninterrupted Mesopotamian plain stretching out before you. The city itself is a collocation of square brick houses and Artuqid architecture, unique in its brutalist design.

Along the stone streets was a market alive with artisans, mostly coffee vendors who had strange machines that turned coffee beans into dust with big metal pistons that would slowly tamp down the coffee in a pit. Every storefront had one of these things, sometimes ornamented, sometimes with a teddy bear on top, forever churning the ground coffee. Surrounding us in the market were coppersmiths and peddlers guiding donkeys laden with goods, all artisans still practising their crafts as though the world had not moved on. However, the donkeys were carrying plastic buckets full of scrap metal rather than woven baskets full of grain.

After darting down an alley, a sculpture of the same minaret we had just passed caught my eye. It had been carved from soap. Two teenage boys were running the shop, and they brought us in. Inside we discovered different varieties of coloured soap, wrapped in plastic and stacked all the way up to the low ceilings. It was clear they were proud of the work they did and offered up each scented variety: Saffron, lavender, chamomile, pistachio, sandalwood and olive oil. They explained the soap process of mixing the herbs with raw liquid soap, pouring it into great slabs on the floor, letting it cool and then dry. After it dried, they would drag a knife through the soap, cutting the slabs into familiarly shaped bars and stamp each with their family’s emblem. I bought a few as gifts and then headed back out to the streets.

Hoping for a view, we set our sights on the castle crowning the city. We climbed to the top of the mesa only to find it blocked by a tangle of barbed wire and instead found ourselves in a lonely cemetery. One man in his mid-30s stood in front of a stone, praying into the headwind, before turning around and offering us a smile and a tour. There was an escape tunnel, he said, originally used for drainage in the castle, but it was damaged during a violent earthquake. He pointed to the areas of the fence knocked over by castle rubble. He pointed out to the Mesopotamian lowlands, stretching to the horizon. This was his home, he explained, from the top of Mardin to the plains below.

Back in town, we stopped at the Kasimiye Medrese, an old Islamic school.

Now, it is empty, but in its heyday, students would have filled its brick corridors with buzzing voices. Inside the courtyard was a pool with a small spout and a slim bridge representing sirat, which in Islam is the bridge you cross after death to enter Paradise. We stopped by a few of the other famous mosques and medreses in town, including the Seyh Cabuk Mosque, the Sehidiye Medrese and the Ulu Cami (the Grand Mosque), all featuring unusual ridged domes and bullet-shaped minarets with odd ledges and spikes.

Deyrulzafaran

Have you heard of Syriac Christians? I had not before I visited this part of the world, so no shame if it is news to you, too. They were some of the first to convert and use a Semitic language, closer to what Jesus and the apostles would have spoken, called Syriac. They have some monasteries outside of town which, when you gaze up at them, stop you in your tracks and catch your eye instantly.

A fabulous example is just a few kilometres outside of Mardin, the Deyrulzafaran Monastery, sometimes known as the “Saffron” Monastery.

Deyrulzafaran looked like a stately library in the same sandy brown as if it had been sculpted from the earth surrounding it. It would not have looked out of place in Tuscany. Leading up to the gateway, a tree-lined path welcomed visitors from the plains. A grand staircase led up to the landing and a huge vaulted doorway.

Inside we found courtyards of stone and olive trees and tiny staircases that led to bell towers and catacombs.

The monastery has 365 rooms — one for each day of the year — and a wild history for a religious site. Before the Syriac Christians used it for their worship, it was a Sumerian temple to a sun god, and before that, a secular Roman citadel.

Dara

Our journey then took us to Dara, a forgotten city made of caves, dilapidated buildings and a deep now-empty reservoir that resembled the Mines of Moria from “The Lord of the Rings.” Dara was a Byzantine city important in the battles against the Persians and used to be one of the most populated places in all of Mesopotamia. Now, it has more or less fallen off the tourist trail. It is fabulous though with its combination of rock-cut caves and ruined waterworks.

We parked, entered and walked past a small village into what looked like a quarry. Inside the quarry, we found a series of holes in the rock faces, resembling Jordan’s Petra but on a smaller scale. Most of the caves were tombs, with shelves inside to place the dead. No bones remain, but one could still feel the sacredness of the place.

Some children were playing on the rocky ruins and they told us to head around the corner away from the main ruins to check out the old cistern. We were glad we took their advice otherwise we would have never found it. We descended around 20 meters (65 feet) into almost total darkness on a narrow stone staircase and looked up, mouths agape. The old cistern’s huge arches hung in the darkness above us, evidence that the ruins above used to house a huge settled population.

Every place we visited represents the scarred evidence of a human civilization older than anything we are familiar or even comfortable with. A vast labyrinth of tunnels, churches and square stone houses all the same colour of the surrounding desert. It is eerie, lonely and made me feel 1,000 years old. Religions were born here I think because once you are done doing agriculture or cleaning, there’s not much else to do except stare out toward the emptiness. Well, it is either stare out and ponder or remember that you have to get back to work. The vacation is over, everyone.

Source: Daily Sabah

This article was first published on 8 November 2017.